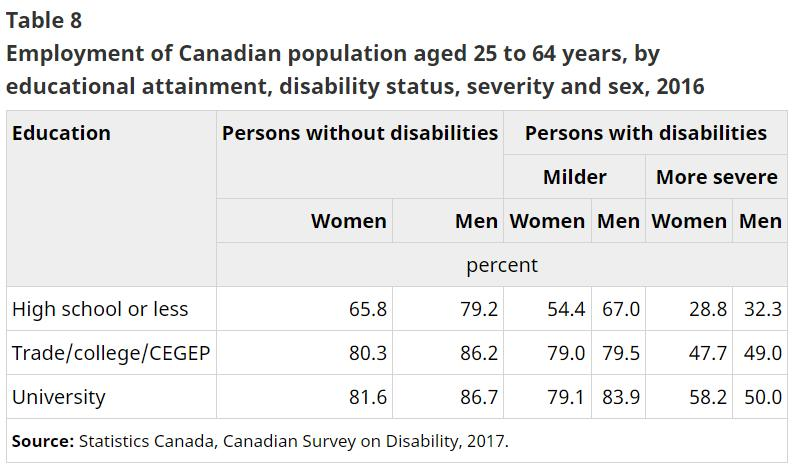

Employment of women without disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 65.8%. Employment of men without disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 79.2%. Employment of women with mild disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 54.4%. Employment of men with mild disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 67%. Employment of women with more severe disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 28.8%. Employment of men with more severe disabilities and a high school diploma or less: 32.3%.

Employment of women without disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 80.3%. Employment of men without disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 86.2%. Employment of women with mild disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 79%. Employment of men with mild disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 79.5%. Employment of women with more severe disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 47.7%. Employment of men with more severe disabilities and a college or technical/trade school certification: 49%.

Employment of women without disabilities and a university degree: 81.6%. Employment of men without disabilities and a university degree: 86.7%. Employment of women with mild disabilities and a university degree: 79.1%. Employment of men with mild disabilities and a university degree: 83.9%. Employment of women with more severe disabilities and a university degree: 58.2%. Employment of men with more severe disabilities and a university degree: 50%.

Federal statistics are clear. The strongest correlated factor of the gap between disabled and non-disabled unemployment in Canada, whether physical or mental disability, is a post-secondary education. Statistics Canada has reported survey after survey that a post-secondary education is a correlation to freedom from poverty, freedom from violence, and freedom from physical and mental illness. For Canadians with disabilities, post-secondary education is an actionable factor that improves all of these outcomes of health and good life.

A person with “severe” disabilities is multiple times more able to access employment if they have a post-secondary education. The employment gap between people without disabilities, and people with “mild” disabilities, who have a post-secondary education, is neglegible; the gap is significant for those without advanced education.

And according to the 2016 Canadian Survey on Disability, it does not matter if that education comes from a trade school, a community college, or the University of Toronto. Learning is learning. With the exception of women with “severe” disabilities, who strongly benefit from a university degree over a trade certificate, the gaps between workers without disabilities and workers with disabilities are all equally mitigated by a post-secondary certification no matter what level of education that may come from.

With this knowledge, now we must turn our research to the barriers faced by people with disabilities in accessing school acceptance and seeing their programs through to the end. We must build solutions that accommodate these barriers and, create post-secondary school environments where these barriers do not exist.